Introduction

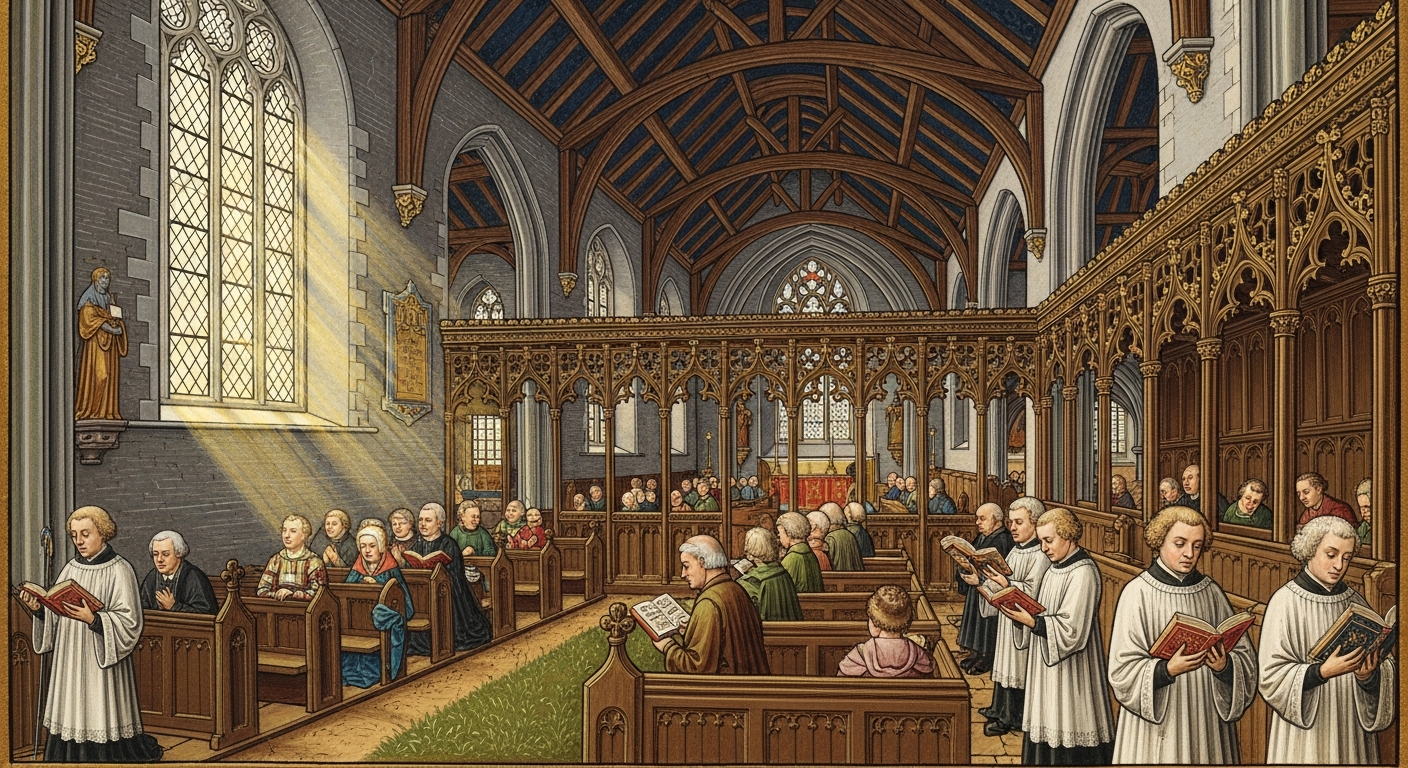

Imagine walking into your local parish church on a Sunday morning in 1549 and hearing the familiar words of worship spoken in English for the first time in over a thousand years. The Latin phrases that had echoed through stone arches since time immemorial were suddenly replaced with the vernacular tongue of ordinary English people. This revolutionary transformation wasn’t merely a linguistic shift, it represented one of the most profound religious and cultural upheavals in English history, mandated by Parliament on 20th January 1549 through the first Act of Uniformity under Edward VI.

The Act established Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer as the sole legal form of worship throughout England, effectively outlawing the traditional Latin Mass and ancient Catholic rituals that had shaped English spiritual life for centuries. This wasn’t simply about translation; it was about fundamentally reimagining how an entire nation would worship, think about God, and understand their place in the cosmos.

Understanding this pivotal moment reveals how religious reform intersected with politics, language, and everyday life in Tudor England, creating ripples that would influence English culture, literature, and identity for generations to come.

Historical Background

The driving force behind this revolutionary act was Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury since 1533, who had been quietly developing Protestant reforms during the latter years of Henry VIII’s reign. When the young Edward VI ascended the throne in 1547 at age nine, Cranmer finally found the political climate necessary to implement his vision of English worship. Working alongside the Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, Cranmer seized this opportunity to advance the Protestant Reformation that Henry VIII had begun for political rather than theological reasons.

The Act of Uniformity passed through Parliament during a period of significant religious and social upheaval. Edward VI’s government was dominated by Protestant reformers who viewed the young king’s reign as a divine opportunity to purge England of what they considered Catholic superstitions and corruptions. The timing was crucial: Henry VIII’s death had removed the primary obstacle to radical religious reform, whilst Edward’s youth meant that determined adults could shape policy without significant royal interference.

Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, officially titled ‘The Book of the Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments, and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, after the Use of the Church of England’, represented years of careful scholarship and theological consideration. Drawing from ancient Christian liturgies, reformed Protestant practices, and his own theological understanding, Cranmer created a worship book that was simultaneously revolutionary and traditional, accessible yet dignified.

The Act itself was remarkably comprehensive, requiring every parish church in England to adopt the new prayer book by Whitsunday 1549. As documented in the Statutes of the Realm, the legislation imposed specific penalties on clergy who refused compliance: fines, imprisonment, and ultimately deprivation of their livings. This wasn’t merely a suggestion from government, it was a legal mandate that would transform the religious landscape of an entire nation.

Significance and Impact

The immediate impact of the Act of Uniformity extended far beyond church walls into the daily lives of ordinary English people. For the first time in their lives, parishioners could understand every word of their religious services. The mysterious Latin phrases that had created a sense of sacred otherness were replaced with familiar English words and concepts. This democratisation of worship fundamentally altered the relationship between clergy and laity, making religious knowledge more accessible whilst potentially diminishing the priest’s role as sole interpreter of divine mysteries.

From a linguistic perspective, the Act’s requirement for English worship contributed significantly to the standardisation and elevation of the English language. Cranmer’s elegant prose in the Book of Common Prayer, with its memorable phrases like ’till death us do part’ and ‘earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust’, enriched English literature and provided a common linguistic foundation for Protestant worship. As noted by scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch in his comprehensive study of Cranmer, the Archbishop’s literary contributions helped establish English as a language worthy of the highest religious expression.

The social and political ramifications were equally profound. The Act represented a clear break with Rome and Catholic tradition, signalling England’s commitment to Protestant reform under Edward VI. However, this religious revolution also created significant resistance, particularly in rural areas where traditional Catholic practices remained deeply embedded in community life. The Western Rebellion of 1549, partly triggered by opposition to the new prayer book, demonstrated that religious change couldn’t be imposed without social consequences.

Perhaps most significantly, the Act established the principle of parliamentary authority over religious practice, a precedent that would shape English constitutional development for centuries. By requiring legislative approval for religious reform, the Act acknowledged Parliament’s role in determining national religious policy, contributing to the gradual shift of power from monarchy to legislature that would characterise later English political development.

Connections and Context

The 1549 Act of Uniformity cannot be understood in isolation from the broader European Reformation movement. Cranmer maintained extensive correspondence with continental reformers like Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli, incorporating their theological insights into his English reforms. The Book of Common Prayer reflected international Protestant thought whilst maintaining distinctly English characteristics, creating a unique Anglican identity that would distinguish the Church of England from both Roman Catholicism and continental Protestantism.

Domestically, the Act occurred during a period of significant social and economic upheaval. Edward VI’s reign witnessed widespread enclosure riots, currency debasement, and social unrest that complicated religious reform efforts. The Pilgrimage of Grace during Henry VIII’s reign had already demonstrated how religious change could trigger broader social rebellion, making the successful implementation of Cranmer’s reforms particularly challenging.

The Act also connected directly to contemporary developments in education and literacy. The requirement for English worship necessitated increased literacy among both clergy and laity, contributing to educational reforms and the proliferation of vernacular religious literature. This created a positive feedback loop: English worship encouraged literacy, which in turn facilitated deeper engagement with Protestant theological texts and ideas.

Modern Relevance and Fascinating Details

Modern readers might be surprised to learn that many phrases from Cranmer’s 1549 Book of Common Prayer continue to influence contemporary English. Beyond the famous wedding and funeral liturgies, expressions like ‘comfortable words’ (meaning consoling, not physically comfortable) and ‘prevent us’ (meaning to go before us, not to hinder) demonstrate how Tudor religious language shaped modern English usage. As a historical fiction author, I find these linguistic survivals particularly fascinating as they provide authentic period flavour for Tudor-era dialogue and narrative.

Did you know that the Act of Uniformity created one of history’s first examples of nationwide consumer protection legislation? By mandating that all prayer books conform to Cranmer’s approved text, the government essentially prevented the sale of unauthorised religious materials, protecting consumers from potentially heretical or illegal purchases. This regulatory approach prefigured modern approaches to standardisation and quality control.

The 1549 Act has gained renewed attention in contemporary discussions about religious freedom, state authority, and cultural change. Modern debates about religious expression in public spaces often reference Tudor precedents, whilst scholars studying rapid social transformation examine how Edward VI’s government managed to implement such comprehensive change across an entire nation without modern communication technologies. The Act provides a fascinating case study in how governments can successfully mandate cultural transformation through legal and institutional mechanisms.

Fiction note: My sequel, Proclamation: Poetry will be the death of me, contains a few scenes starring Thomas Cranmer, and still more where Dee is finding/fetching a cartload of Common Prayer books. You can check it out at the link, or look for blog posts in the Predestination category for possible excerpts from that book.

Conclusion

The Act of Uniformity passed on 20th January 1549 represents far more than a simple change in religious practice, it marked a fundamental transformation in English culture, language, and identity. Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, mandated by this legislation, created a distinctly English form of worship that would influence the nation’s religious and literary development for centuries. The Act’s requirement for vernacular worship democratised religious participation whilst establishing important constitutional precedents about parliamentary authority over religious matters.

Understanding this pivotal moment in Tudor history illuminates how religious, political, and cultural changes intersected during one of England’s most dynamic periods. Whether you’re interested in the development of the English language, the mechanics of social transformation, or the intricate politics of Tudor religious reform, the 1549 Act of Uniformity offers rich insights into how nations negotiate profound cultural change. For those seeking to understand the foundations of Anglican worship or the broader trajectory of English Protestant development, this legislation represents an essential starting point for deeper historical exploration.